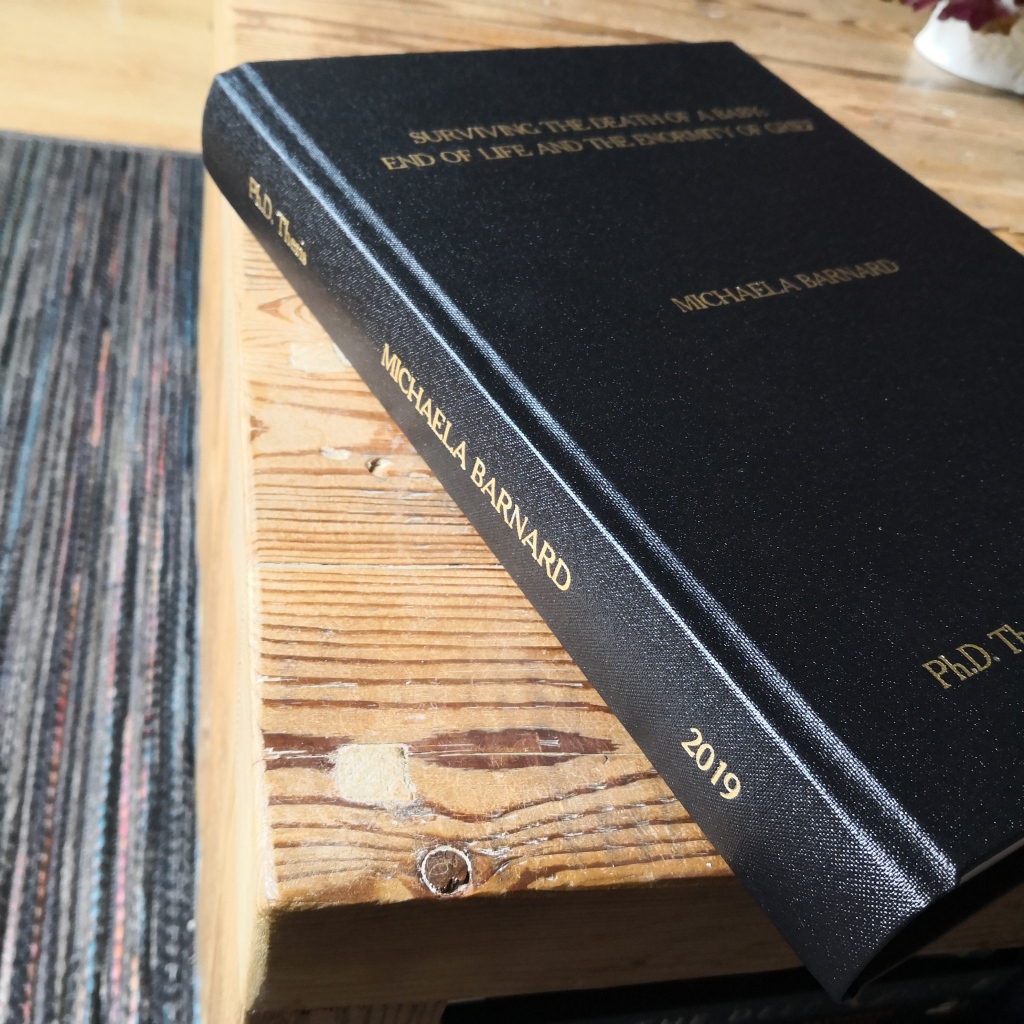

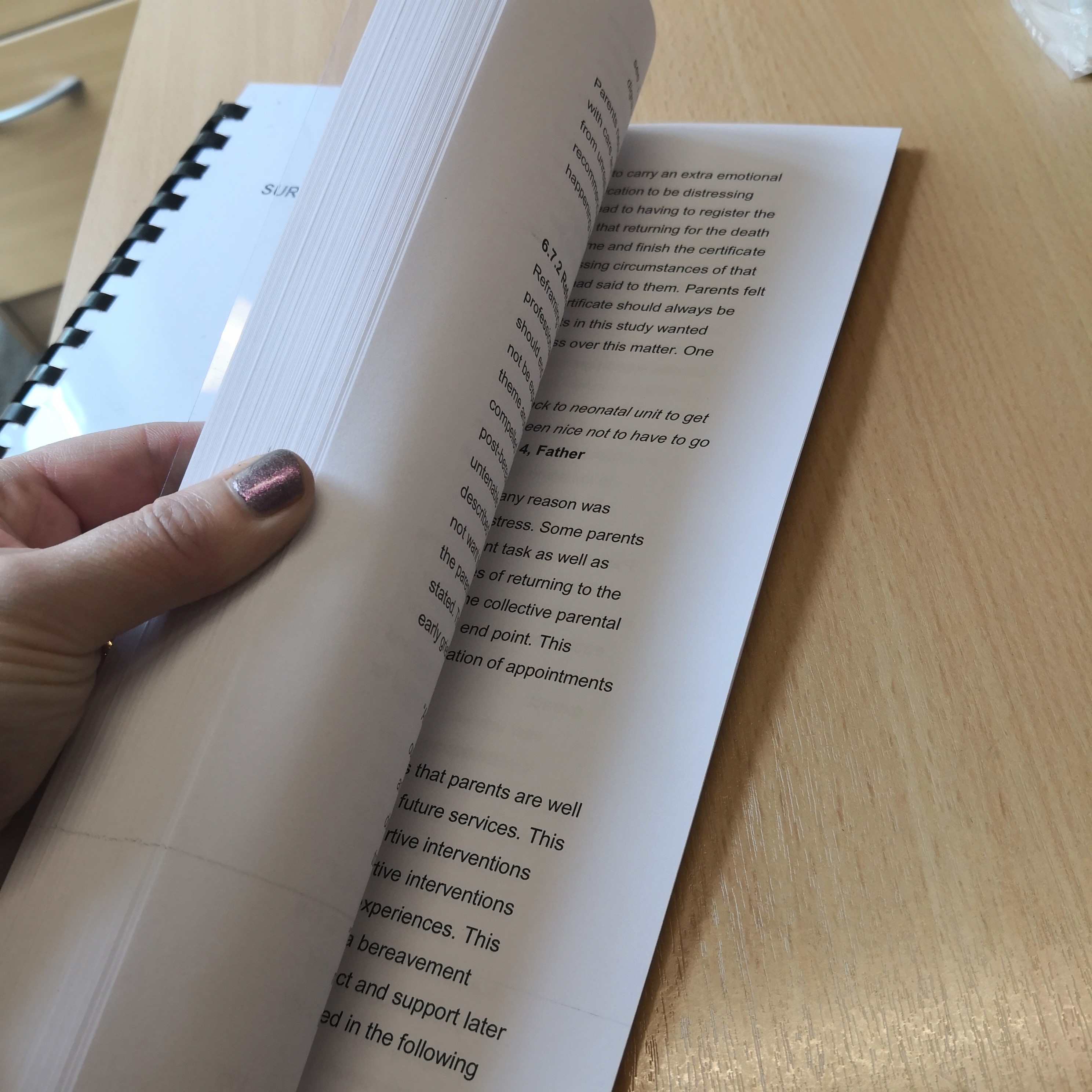

I thought I’d write an update about life with long covid, a long term condition and living with hidden disabilities while trying to work full time, be a partner, mum and academic who cares about their career. This last 18 months has been a challenge but with lots of good parts and opportunities. I’m an inherently positive person, taking each new day as it arrives but I must admit to some faltering moments in recent times.

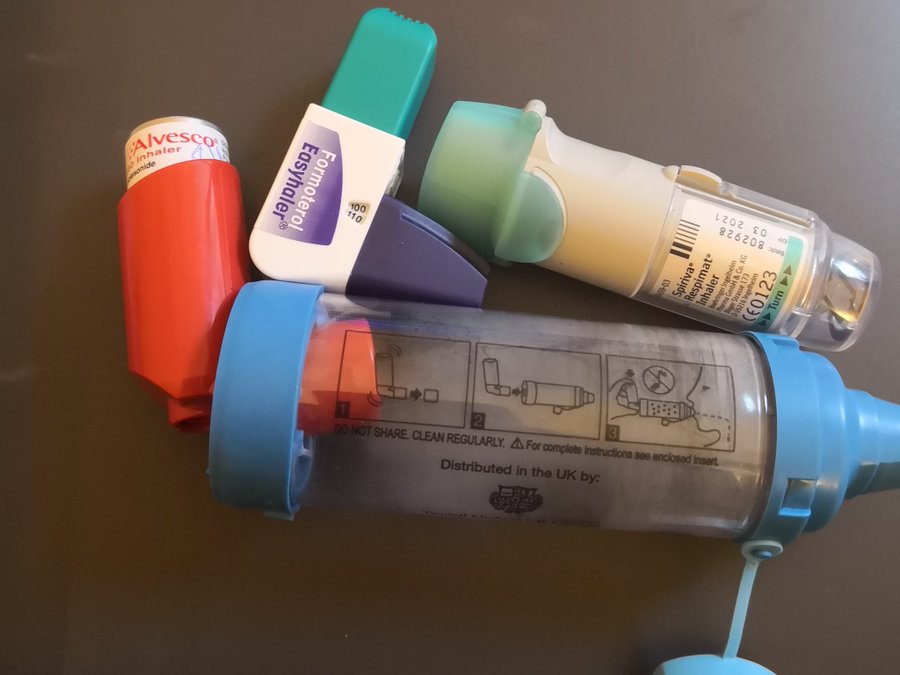

If you don’t know, I had a close call with covid before vaccinations were availabile and nearly lost my life. It left me with long covid and I’ve had such a variety of symptoms and physiological disruptions as a result of it. I’m still having new things pop up; it’s certainly a ride. I have severe asthma as a pre-existing condition, so that’s definitely complicated things.

Covid left me with :

– long covid

– breathlessness

– crippling fatigue

– sleep disruptions

– a change in ability to exercise

– irreversible loss of hearing in my left ear

– gastrointestinal disruptions

– menstrual disruption that’s now resolved

– ongoing mild trauma from covid hospitalisation experiences

Covid also gifted me with two cancer scares in the last 12 months. The first was a large lump on my neck that developed and didn’t go down. I went through scans and tests for lymphoma. Thankfully that was shown to be an enlarged lymph node that is still there but somewhat smaller. The second was a need to check if I had a brain tumour of some description as the sudden and irreversible hearing loss was unusual but I’ve recently had the all clear on that following an MRI of my ear and brain. The ENT consultant agrees the hearing loss is from the acute covid infection and severity of my illness at the time.

Over these months, it’s often been hard to access healthcare with my various issues. As a champion of the NHS and my colleagues there, I’ve had to be patient but I’ve also experienced frustration, as at first little was known about long covid. I found a great health coach to help me get active to some extent. I have had a superb experience with the long covid service in my locality, however. I had a period of sessions with a physiotherapist to get me walking and exercising better while closely monitoring my heart rate and oxygen saturations. Then I had eight weeks in a long covid online therapy group (a bit like CBT) to help you understand your limits, what you can do to help symptoms and what to do to preserve energy. It was run by a pain team, using the techniques developed for those with chronic pain and it was excellent. One of the best things about that was that I finally met other people with long covid and it was validating even though we all had different symptoms and experiences. I had a really good cry after our first long covid group meeting because I finally didn’t feel like the only person walking this journey. We have a little WhatsApp group chat now and they are the best people.

Things that have helped me adjust to this new and more limited me are some adaptations in my work life including working at home when I can, classrooms as near to my office as possible, using captioning in online meetings and teaching and a supportive boss. Things that have helped my wider life is firstly, a hearing aid which has limitations but does help, my family’s support and knowing I can chat to another person with long covid if I need to. I have a great asthma consultant who has been compassionate about the extra burden long covid brings to my asthma picture and he continues to try and improve my quality of life (thank you, Stephen).

I’ve since had a second bout of covid and while it was tougher than I expected now I’m fully vaccinated, I wasn’t hospitalised this time and I don’t feel any worse than before now that I’m recovered.

I am managing to carry out my full time job but there are times where it is all I can do in that day, then just sit in the evening when I’d like to walk or do something. I often feel inadequate about things I need to do to further my academic career, get papers finished and published etc but I do have to take it one day at a time and manage what I can.

Here’s the newest good bit. One of my fellow long covid buddies clued us into some probiotics that were part of a long covid study (link below to the study). I’ve now been taking them for about 9 weeks and I am seeing improvements in my fatigue and I can walk further and manage a day out without complete crash most of the time. Some of my friends have had even better results. I’ll be keeping an eye on the science on this one. The probiotics seem to have settled my gastrointestinal problems to an extent too. The breathlessness that comes on easily still persists.

https://www.mdpi.com/2673-8112/2/4/31

The future looks brighter than it did six months ago but I know that long covid doesn’t seem to be going anywhere and as such it’s a hidden disability for me and many others.

Thank for for reading. By reading this, you’re understanding what life can be like for millions of people with long covid across the globe.

Michaela